Modern historiographical practice distinguishes chattel (personal possession) slavery from land-bonded groups such as the penestae of Thessaly or the Spartan helots, who were more like medieval serfs (an enhancement to real estate). The chattel slave is an individual deprived of liberty and forced to submit to an owner, who may buy, sell or lease them like any other chattel.

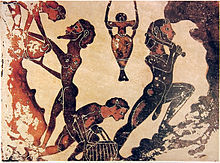

The academic study of slavery in ancient Greece is beset by significant methodological problems. Documentation is disjointed and very fragmented, focusing primarily on Athens. No treatises are specifically devoted to the subject, and jurisprudence was interested in slavery only inasmuch as it provided a source of revenue. Comedies and tragedies represented stereotypes while iconography made no substantial differentiation between slaves and craftsmen.

Terminology

Other terms used were less precise and required context:

-

- θεράπων / therapōn – At the time of Homer, the word meant "squire" (Patroclus was referred to as the therapōn of Achilles[11] and Meriones that of Idomeneus[12]); during the classical age, it meant "servant".[13]

- ἀκόλουθος / akolouthos – literally, "the follower" or "the one who accompanies". Also, the diminutive ἀκολουθίσκος, used for page boys.[14]

- παῖς / pais – literally "child", used in the same way as "houseboy",[15] also used in a derogatory way to call adult slaves.[16]

- σῶμα / sōma – literally "body", used in the context of emancipation.[17]

Origins of slavery

There is no continuity between the Mycenaean era and the time of Homer, where social structures reflected those of the Greek dark ages. The terminology differs: the slave is no longer do-e-ro (doulos) but dmōs.[22] In the Iliad, slaves are mainly women taken as booty of war,[23] while men were either ransomed[24] or killed on the battlefield. In the Odyssey, the slaves also seem to be mostly women.[25] These slaves were servants[26] and sometimes concubines.[27] There were some male slaves, especially in the Odyssey, a prime example being the swineherd Eumaeus. The slave was distinctive in being a member of the core part of the oikos ("family unit", "household"): Laertes eats and drinks with his servants;[28] in the winter, he sleeps in their company.[29] The term dmōs is not considered pejorative, and Eumaeus, the "divine" swineherd,[30] bears the same Homeric epithet as the Greek heroes.[31] Slavery remained, however, a disgrace. Eumaeus himself declares, "Zeus, of the far-borne voice, takes away the half of a man's virtue, when the day of slavery comes upon him".[32] · [31]

It is difficult to determine when slave trading began in the archaic period. In Works and Days (8th century BC), Hesiod owns numerous dmōes[33] although their status is unclear. The presence of douloi is confirmed by lyric poets such as Archilochus or Theognis of Megara.[31] According to epigraphic evidence, the homicide law of Draco (c. 620 BC) mentioned slaves.[34] According to Plutarch,[35] Solon (c. 594-593 BC) forbade slaves from practising gymnastics and pederasty. By the end of the period, references become more common. Slavery becomes prevalent at the very moment when Solon establishes the basis for Athenian democracy. Classical scholar Moses Finley likewise remarks that Chios, which, according to Theopompus,[36] was the first city to organize a slave trade, also enjoyed an early democratic process (in the 6th century BC). He concludes that "one aspect of Greek history, in short, is the advance hand in hand, of freedom and slavery."[37]

Economic role

The principal use of slavery was in agriculture, the foundation of the Greek economy. Some small landowners might own one slave, or even two.[40] An abundant literature of manuals for landowners (such as the Economy of Xenophon or that of Pseudo-Aristotle) confirms the presence of dozens of slaves on the larger estates; they could be common labourers or foremen. The extent to which slaves were used as a labour force in farming is disputed.[41] It is certain that rural slavery was very common in Athens, and that ancient Greece did not know of the immense slave populations found on the Roman latifundia.[42]

Slave labour was prevalent in mines and quarries, which had large slave populations, often leased out by rich private citizens. The strategos Nicias leased a thousand slaves to the silver mines of Laurium in Attica; Hipponicos, 600; and Philomidès, 300. Xenophon[43] indicates that they received one obolus per slave per day, amounting to 60 drachmas per year. This was one of the most prized investments for Athenians. The number of slaves working in the Laurium mines or in the mills processing ore has been estimated at 30,000.[44] Xenophon suggested that the city buy a large number of slaves, up to three state slaves per citizen, so that their leasing would assure the upkeep of all the citizens.[43]

Slaves were also used as craftsmen and tradespersons. As in agriculture, they were used for labour that was beyond the capability of the family. The slave population was greatest in workshops: the shield factory of Lysias employed 120 slaves,[45] and the father of Demosthenes owned 32 cutlers and 20 bedmakers.[46]

Slaves were also employed in the home. The domestic's main role was to stand in for his master at his trade and to accompany him on trips. In time of war he was batman to the hoplite. The female slave carried out domestic tasks, in particular bread baking and textile making. Only the poorest citizens did not possess a domestic slave.[47]

Demographics

Population

According to the literature, it appears that the majority of free Athenians owned at least one slave. Aristophanes, in Plutus, portrays poor peasants who have several slaves; Aristotle defines a house as containing freemen and slaves.[51] Conversely, not owning even one slave was a clear sign of poverty. In the celebrated discourse of Lysias For the Invalid, a cripple pleading for a pension explains "my income is very small and now I'm required to do these things myself and do not even have the means to purchase a slave who can do these things for me."[52] However, the huge slave populations of the Romans were unknown in ancient Greece. When Athenaeus[53] cites the case of Mnason, friend of Aristotle and owner of a thousand slaves, this appears to be exceptional. Plato, owner of five slaves at the time of his death, describes the very rich as owning 50 slaves.[54]

Thucydides estimates that the isle of Chios had proportionally the largest number of slaves.[55]

Sources of supply

| Slavery |

|---|

|

War

By the rules of war of the period, the victor possessed absolute rights over the vanquished, whether they were soldiers or not.[56] Enslavement, while not systematic, was common practice. Thucydides recalls that 7,000 inhabitants of Hyccara in Sicily were taken prisoner by Nicias and sold for 120 talents in the neighbouring village of Catania.[57] Likewise in 348 BC the population of Olynthus was reduced to slavery, as was that of Thebes in 335 BC by Alexander the Great and that of Mantineia by the Achaean League.[58]The existence of Greek slaves was a constant source of discomfort for free Greeks. The enslavement of cities was also a controversial practice. Some generals refused, such as the Spartans Agesilaus II[59] and Callicratidas.[60] Some cities passed accords to forbid the practice: in the middle of the 3rd century BC, Miletus agreed not to reduce any free Knossian to slavery, and vice versa.[58] Conversely, the emancipation by ransom of a city that had been entirely reduced to slavery carried great prestige: Cassander, in 316 BC, restored Thebes.[61] Before him, Philip II of Macedon enslaved and then emancipated Stageira.[62]

Piracy and banditry

Piracy and banditry provided a significant and consistent supply of slaves,[63] though the significance of this source varied according to era and region.[64] Pirates and brigands would demand ransom whenever the status of their catch warranted it. Whenever ransom was not paid or not warranted, captives would be sold to a trafficker.[65] In certain areas, piracy was practically a national specialty, described by Thucydides as "the old-fashioned" way of life.[66] Such was the case in Acarnania, Crete, and Aetolia. Outside of Greece, this was also the case with Illyrians, Phoenicians, and Etruscans. During the Hellenistic period, Cilicians and the mountain peoples from the coasts of Anatolia could also be added to the list. Strabo explains the popularity of the practice among the Cilicians by its profitability; Delos, not far away, allowed for "moving a myriad of slaves daily".[67] The growing influence of the Roman Republic, a large consumer of slaves, led to development of the market and an aggravation of piracy.[68] In the 1st century BC, however, the Romans largely eradicated piracy to protect the Mediterranean trade routes.[69]Slave trade

There was slave trade between kingdoms and states of the wider region. The fragmentary list of slaves confiscated from the property of the mutilators of the Hermai mentions 32 slaves whose origin have been ascertained: 13 came from Thrace, 7 from Caria, and the others came from Cappadocia, Scythia, Phrygia, Lydia, Syria, Ilyria, Macedon and Peloponnese.[70] Local professionals sold their own people to Greek slave merchants. The principal centres of the slave trade appear to have been Ephesus, Byzantium, and even faraway Tanais at the mouth of the Don. Some "barbarian" slaves were victims of war or localised piracy, but others were sold by their parents.[71] There is a lack of direct evidence of slave traffic, but corroborating evidence exists. Firstly, certain nationalities are consistently and significantly represented in the slave population, such as the corps of Scythian archers employed by Athens as a police force—originally 300, but eventually nearly a thousand.[72] Secondly, the names given to slaves in the comedies often had a geographical link; thus Thratta, used by Aristophanes in The Wasps, The Acharnians, and Peace, simply signified Thracian woman.[73] Finally, the nationality of a slave was a significant criterion for major purchasers; the ancient advice was not to concentrate too many slaves of the same origin in the same place, in order to limit the risk of revolt.[74] It is also probable that, as with the Romans, certain nationalities were considered more productive as slaves than others.The price of slaves varied in accordance with their ability. Xenophon valued a Laurion miner at 180 drachmas;[43] while a workman at major works was paid one drachma per day. Demosthenes' father's cutlers were valued at 500 to 600 drachmas each.[75] Price was also a function of the quantity of slaves available; in the 4th century BC they were abundant and it was thus a buyer's market. A tax on sale revenues was levied by the market cities. For instance, a large slave market was organized during the festivities at the temple of Apollo at Actium. The Acarnanian League, which was in charge of the logistics, received half of the tax proceeds, the other half going to the city of Anactorion, of which Actium was a part.[76] Buyers enjoyed a guarantee against latent defects; the transaction could be invalidated if the bought slave turned out to be crippled and the buyer had not been warned about it.[77]

Natural growth

Xenophon advised that male and female slaves should be lodged separately, that "…nor children born and bred by our domestics without our knowledge and consent—no unimportant matter, since, if the act of rearing children tends to make good servants still more loyally disposed, cohabiting but sharpens ingenuity for mischief in the bad."[80] The explanation is perhaps economic; even a skilled slave was cheap,[81] so it may have been cheaper to purchase a slave than to raise one.[82] Additionally, childbirth placed the slave-mother's life at risk, and the baby was not guaranteed to survive to adulthood.[83]

Houseborn slaves (oikogeneis) often constituted a privileged class. They were, for example, entrusted to take the children to school; they were "pedagogues" in the first sense of the term.[84] Some of them were the offspring of the master of the house, but in most cities, notably Athens, a child inherited the status of its mother.[83]

Status of slaves

The Greeks had many degrees of enslavement. There was a multitude of categories, ranging from free citizen to chattel slave, and including Penestae or helots, disenfranchised citizens, freedmen, bastards, and metics.[85] The common ground was the deprivation of civic rights.Moses Finley proposed a set of criteria for different degrees of enslavement:[86]

-

- had no rights

- Right to own property

- Authority over the work of another

- Power of punishment over another

- Legal rights and duties (liability to arrest and/or arbitrary punishment, or to litigate)

- Familial rights and privileges (marriage, inheritance, etc.)

- Possibility of social mobility (manumission or emancipation, access to citizen rights)

- Religious rights and obligations

- Military rights and obligations (military service as servant, heavy or light soldier, or sailor)

Athenian slaves

Isocrates claimed that "not even the most worthless slave can be put to death without trial";[91] the master's power over his slave was not absolute.[92] Draco's law apparently punished with death the murder of a slave; the underlying principle was: "was the crime such that, if it became more widespread, it would do serious harm to society?"[93] The suit that could be brought against a slave's killer was not a suit for damages, as would be the case for the killing of cattle, but a δίκη φονική (dikē phonikē), demanding punishment for the religious pollution brought by the shedding of blood.[94] In the 4th century BC, the suspect was judged by the Palladion, a court which had jurisdiction over unintentional homicide;[95] the imposed penalty seems to have been more than a fine but less than death—maybe exile, as was the case in the murder of a Metic.[94]

Slaves could not own property, but their masters often let them save up to purchase their freedom,[97] and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves: if a person struck what appeared to be a slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It astonished other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves.[98] Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen at the battle of Marathon, and the monuments memorialize them.[99] It was formally decreed before the battle of Salamis that the citizens should "save themselves, their women, children, and slaves".[100]

Slaves had special sexual restrictions and obligations. For example, a slave could not engage free boys in pederastic relationships ("A slave shall not be the lover of a free boy nor follow after him, or else he shall receive fifty blows of the public lash."), and they were forbidden from the palaestrae ("A slave shall not take exercise or anoint himself in the wrestling-schools."). Both laws are attributed to Solon.[101] Fathers wanting to protect their sons from unwanted advances provided them with a slave guard, called a paidagogos, to escort the boy in his travels.

The sons of vanquished foes would be enslaved and often forced to work in male brothels, as in the case of Phaedo of Elis, who at the request of Socrates was bought and freed from such an enterprise by the philosopher's rich friends.[102] On the other hand, it is attested in sources that the rape of slaves was persecuted, at least occasionally.[103]

Slaves in Gortyn

Slaves did have the right to possess a house and livestock, which could be transmitted to descendants, as could clothing and household furnishings.[105] Their family was recognized by law: they could marry, divorce, write a testament and inherit just like free men.[107]

A specific case: debt slavery

Prior to its interdiction by Solon, Athenians practiced debt enslavement: a citizen incapable of paying his debts became "enslaved" to the creditor.[108] The exact nature of this dependency is a much controversial issue among modern historians: was it truly slavery or another form of bondage? However, this issue primarily concerned those peasants known as "hektēmoroi"[109] working leased land belonging to rich landowners and unable to pay their rents. In theory, those so enslaved would be liberated when their original debts were repaid. The system was developed with variants throughout the Near East and is cited in the Bible.[110]Solon put an end to it with the σεισάχθεια / seisachtheia, liberation of debts, which prevented all claim to the person by the debtor and forbade the sale of free Athenians, including by themselves. Aristotle in his Constitution of the Athenians quotes one of Solon's poems:

And many a man whom fraud or law had soldThough much of Solon's vocabulary is that of "traditional" slavery, servitude for debt was at least different in that the enslaved Athenian remained an Athenian, dependent on another Athenian, in his place of birth.[112] It is this aspect which explains the great wave of discontent with slavery of the 6th century BC, which was not intended to free all slaves but only those enslaved by debt.[113] The reforms of Solon left two exceptions: the guardian of an unmarried woman who had lost her virginity had the right to sell her as a slave,[114] and a citizen could "expose" (abandon) unwanted newborn children.[115]

Far from his god-built land, an outcast slave,

I brought again to Athens; yea, and some,

Exiles from home through debt’s oppressive load,

Speaking no more the dear Athenian tongue,

But wandering far and wide, I brought again;

And those that here in vilest slavery (douleia)

Crouched ‘neath a master’s (despōtes) frown, I set them free.[111]

Manumission

The practice of manumission is confirmed to have existed in Chios from the 6th century BC.[116] It probably dates back to an earlier period, as it was an oral procedure. Informal emancipations are also confirmed in the classical period. It was sufficient to have witnesses, who would escort the citizen to a public emancipation of his slave, either at the theatre or before a public tribunal.[117] This practice was outlawed in Athens in the middle of the 6th century BC to avoid public disorder.[117]The practice became more common in the 4th century BC and gave rise to inscriptions in stone which have been recovered from shrines such as Delphi and Dodona. They primarily date to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and the 1st century AD. Collective manumission was possible; an example is known from the 2nd century BC in the island of Thasos. It probably took place during a period of war as a reward for the slaves' loyalty,[118] but in most cases the documentation deals with a voluntary act on the part of the master (predominantly male, but in the Hellenistic period also female).

The slave was often required to pay for himself an amount at least equivalent to his street value. To this end they could use their savings or take a so-called "friendly" loan (ἔρανος / eranos) from their master, a friend or a client like the hetaera Neaira did.[119]

Emancipation was often of a religious nature, where the slave was considered to be "sold" to a deity, often Delphian Apollo,[120] or was consecrated after his emancipation. The temple would receive a portion of the monetary transaction and would guarantee the contract. The manumission could also be entirely civil, in which case the magistrate played the role of the deity.[121]

The slave's freedom could be either total or partial, at the master's whim. In the former, the emancipated slave was legally protected against all attempts at re-enslavement—for instance, on the part of the former master's inheritors.[122] In the latter case, the emancipated slave could be liable to a number of obligations to the former master. The most restrictive contract was the paramone, a type of enslavement of limited duration during which time the master retained practically absolute rights.[123]

In regard to the city, the emancipated slave was far from equal to a citizen by birth. He was liable to all types of obligations, as one can see from the proposals of Plato in The Laws:[124] presentation three times monthly at the home of the former master, forbidden to become richer than him, etc. In fact, the status of emancipated slaves was similar to that of metics, the residing foreigners, who were free but did not enjoy a citizen's rights.[125]

Spartan slaves

Spartan citizens used helots, a dependent group collectively owned by the state. It is uncertain whether they had chattel slaves as well. There are mentions of people manumitted by Spartans, which was supposedly forbidden for helots, or sold outside of Lakonia: the poet Alcman;[126] a Philoxenos from Cytherea, reputedly enslaved with all his fellow citizens when his city was conquered, later sold to an Athenian;[127] a Spartan cook bought by Dionysius the Elder or by a king of Pontus, both versions being mentioned by Plutarch;[128] and the famous Spartan nurses, much appreciated by Athenian parents.[129]Some texts mention both slaves and helots, which seems to indicate that they were not the same thing. Plato in Alcibiades I cites "the ownership of slaves, and notably helots" among the Spartan riches,[130] and Plutarch writes about "slaves and helots".[131] Finally, according to Thucydides, the agreement that ended the 464 BC revolt of helots stated that any Messenian rebel who might hereafter be found within the Peloponnese was "to be the slave of his captor", which means that the ownership of chattel slaves was not illegal at that time.

Most historians thus concur that chattel slaves were indeed used in the Greek city-state of Sparta, at least after the Lacedemonian victory of 404 BC against Athens, but not in great numbers and only among the upper classes.[132] As was in the other Greek cities, chattel slaves could be purchased at the market or taken in war.

Slavery conditions

Greek literature abounds with scenes of slaves being flogged; it was a means of forcing them to work, as were control of rations, clothing, and rest. This violence could be meted out by the master or the supervisor, who was possibly also a slave. Thus, at the beginning of Aristophanes' The Knights (4–5), two slaves complain of being "bruised and thrashed without respite" by their new supervisor. However, Aristophanes himself cites what is a typical old saw in ancient Greek comedy:

"He also dismissed those slaves who kept on running off, or deceiving someone, or getting whipped. They were always led out crying, so one of their fellow slaves could mock the bruises and ask then: 'Oh you poor miserable fellow, what's happened to your skin? Surely a huge army of lashes from a whip has fallen down on you and laid waste your back?'"[136]The condition of slaves varied very much according to their status; the mine slaves of Laureion and the pornai (brothel prostitutes) lived a particularly brutal existence, while public slaves, craftsmen, tradesmen and bankers enjoyed relative independence.[137] In return for a fee (ἀποφορά / apophora) paid to their master, they could live and work alone.[138] They could thus earn some money on the side, sometimes enough to purchase their freedom. Potential emancipation was indeed a powerful motivator, though the real scale of this is difficult to estimate.[139]

Ancient writers considered that Attic slaves enjoyed a "peculiarly happy lot":[140] Pseudo-Xenophon deplores the liberties taken by Athenian slaves: "as for the slaves and Metics of Athens, they take the greatest licence; you cannot just strike them, and they do not step aside to give you free passage".[141] This alleged good treatment did not prevent 20,000 Athenian slaves from running away at the end of the Peloponnesian War at the incitement of the Spartan garrison at Attica in Decelea.[142] These were principally skilled artisans (kheirotekhnai), probably among the better-treated slaves. The title of a 4th-century comedy by Antiphanes, The Runaway-catcher (Δραπεταγωγός),[143] suggests that slave flight was not uncommon.[144]

Conversely, there are no records of a large-scale Greek slave revolt comparable to that of Spartacus in Rome.[145] It can probably be explained by the relative dispersion of Greek slaves, which would have prevented any large-scale planning.[146] Slave revolts were rare, even in Rome. Individual acts of rebellion of slaves against their master, though scarce, are not unheard of; a judicial speech mentions the attempted murder of his master by a boy slave, not 12 years old.[147]

Views of Greek slavery

Historical views

During the classical period, the main justification for slavery was economic.[149] From a philosophical point of view, the idea of "natural" slavery emerged at the same time; thus, as Aeschylus states in The Persians, the Greeks "[o]f no man are they called the slaves or vassals",[150] while the Persians, as Euripides states in Helen, "are all slaves, except one" — the Great King.[151] Hippocrates theorizes about this latent idea at the end of the 5th century BC. According to him, the temperate climate of Anatolia produced a placid and submissive people.[152] This explanation is reprised by Plato,[153] then Aristotle in Politics,[154] where he develops the concept of "natural slavery": "for he that can foresee with his mind is naturally ruler and naturally master, and he that can do these things with his body is subject and naturally a slave."[155] As opposed to an animal, a slave can comprehend reason but "…has not got the deliberative part at all."[156]

Alcidamas, at the same time as Aristotle, took the view: "nature has made nobody a slave".[157]

In parallel, the concept that all men, whether Greek or barbarian, belonged to the same race was being developed by the Sophists[158] and thus that certain men were slaves although they had the soul of a freeman and vice versa.[159] Aristotle himself recognized this possibility and argued that slavery could not be imposed unless the master was better than the slave, in keeping with his theory of "natural" slavery.[160] The Sophists concluded that true servitude was not a matter of status but a matter of spirit; thus, as Menander stated, "be free in the mind, although you are slave: and thus you will no longer be a slave".[161] This idea, repeated by the Stoics and the Epicurians, was not so much an opposition to slavery as a trivialisation of it.[162]

The Greeks could not comprehend an absence of slaves. Slaves exist even in the "Cloudcuckooland" of Aristophanes' The Birds as well as in the ideal cities of Plato's Laws or Republic.[163] The utopian cities of Phaleas of Chalcedon and Hippodamus of Miletus are based on the equal distribution of property, but public slaves are used respectively as craftsmen[164] and land workers.[165] The "reversed cities" placed women in power or even saw the end of private property, as in Lysistrata or Assemblywomen, but could not picture slaves in charge of masters. The only societies without slaves were those of the Golden Age, where all needs were met without anyone having to work. In this type of society, as explained by Plato,[166] one reaped generously without sowing. In Telekleides' Amphictyons[167] barley loaves fight with wheat loaves for the honour of being eaten by men. Moreover, objects move themselves—dough kneads itself, and the jug pours itself. Similarly, Aristotle said that slaves would not be necessary "if every instrument could accomplish its own work... the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them", like the legendary constructs of Daedalus and Hephaestus.[168] Society without slaves is thus relegated to a different time and space. In a "normal" society, one needs slaves.

Modern views

In the 19th century, a politico-economic discourse emerged. It concerned itself with distinguishing the phases in the organisation of human societies and correctly identifying the place of Greek slavery. The influence of Marx is decisive; for him the ancient society was characterized by development of private ownership and the dominant (and not secondary as in other pre-capitalist societies) character of slavery as a mode of production.[170] The Positivists represented by the historian Eduard Meyer (Slavery in Antiquity, 1898) were soon to oppose the Marxist theory. According to him slavery was the foundation of Greek democracy. It was thus a legal and social phenomenon, and not economic.[171]

Current historiography developed in the 20th century; led by authors such as Joseph Vogt, it saw in slavery the conditions for the development of elites. Conversely, the theory also demonstrates an opportunity for slaves to join the elite. Finally, Vogt estimates that modern society, founded on humanist values, has surpassed this level of development.[172]

In 2011, Greek slavery remains the subject of historiographical debate, on two questions in particular: can it be said that ancient Greece was a "slave society", and did Greek slaves comprise a social class?[173]

Pericles, the Delian League, and the Athenian Golden Age

Pericles

https://youtu.be/iwHNZVy9p_c

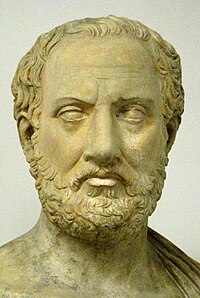

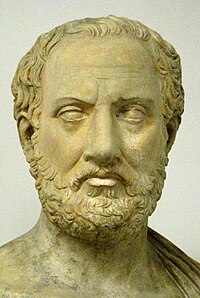

| Thucydides | |

|---|---|

Plaster cast bust of Thucydides (in the Pushkin Museum). From a Roman copy (located at Holkham Hall) of an early 4th Century BC Greek original.

|

|

| Native name | Θουκυδίδης |

| Born | c. 460 BC Halimous (modern Alimos) |

| Died | c. 400 BC (aged approximately 60) Athens |

| Ethnicity | Greek |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Notable work | History of the Peloponnesian War |

| Relatives | Olorus (father) |

He has also been called the father of the school of political realism, which views the political behavior of individuals and the subsequent outcome of relations between states as ultimately mediated by and constructed upon the emotions of fear and self-interest.[3] His text is still studied at both universities and advanced military colleges worldwide.[4] The Melian dialogue remains a seminal work of international relations theory while Pericles' Funeral Oration is widely studied in political theory, history, and classical studies.

More generally, Thucydides showed an interest in developing an understanding of human nature to explain behaviour in such crises as plague, massacres, as in that of the Melians, and civil war.

Life

In spite of his stature as a historian, modern historians know relatively little about Thucydides's life. The most reliable information comes from his own History of the Peloponnesian War, which expounds his nationality, paternity and native locality. Thucydides informs us that he fought in the war, contracted the plague and was exiled by the democracy. He may have also been involved in quelling the Samian Revolt.[5]Evidence from the Classical period

Thucydides identifies himself as an Athenian, telling us that his father's name was Olorus and that he was from the Athenian deme of Halimous.[6] He survived the Plague of Athens[7] that killed Pericles and many other Athenians. He also records that he owned gold mines at Scapte Hyle (literally: "Dug Woodland"), a coastal area in Thrace, opposite the island of Thasos.[8]Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance, and news of its fall caused great consternation in Athens.[11] It was blamed on Thucydides, although he claimed that it was not his fault and that he had simply been unable to reach it in time. Because of his failure to save Amphipolis, he was sent into exile:[12]

I lived through the whole of it, being of an age to comprehend events, and giving my attention to them in order to know the exact truth about them. It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly.Using his status as an exile from Athens to travel freely among the Peloponnesian allies, he was able to view the war from the perspective of both sides. During his exile from Athens, Thucydides wrote his most famous work "History of the Peloponnesian War." Because he was in exile during this time, he was free to speak his mind. He also conducted important research for his history during this time, having claimed that he pursued the project as he thought it would be one of the greatest wars waged among the Greeks in terms of scale. This is all that Thucydides wrote about his own life, but a few other facts are available from reliable contemporary sources. Herodotus wrote that the name Όloros, Thucydides's father's name, was connected with Thrace and Thracian royalty.[13] Thucydides was probably connected through family to the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, and his son Cimon, leaders of the old aristocracy supplanted by the Radical Democrats. Cimon's maternal grandfather's name was also Olorus, making the connection exceedingly likely. Another Thucydides lived before the historian and was also linked with Thrace, making a family connection between them very likely as well. Finally, Herodotus confirms the connection of Thucydides's family with the mines at Scapté Hýlē.[14]

Combining all the fragmentary evidence available, it seems that his family had owned a large estate in Thrace, one that even contained gold mines, and which allowed the family considerable and lasting affluence. The security and continued prosperity of the wealthy estate must have necessitated formal ties with local kings or chieftains, which explains the adoption of the distinctly Thracian royal name "Όloros" into the family. Once exiled, Thucydides took permanent residence in the estate and, given his ample income from the gold mines, he was able to dedicate himself to full-time history writing and research, including many fact-finding trips. In essence, he was a well-connected gentleman of considerable resources who, by then retired from the political and military spheres, decided to fund his own historical project.

Later sources

The remaining evidence for Thucydides's life comes from rather less reliable later ancient sources. According to Pausanias, someone named Oenobius was able to get a law passed allowing Thucydides to return to Athens, presumably sometime shortly after the city's surrender and the end of the war in 404 BC.[15] Pausanias goes on to say that Thucydides was murdered on his way back to Athens. Many doubt this account, seeing evidence to suggest he lived as late as 397 BC. Plutarch claims that his remains were returned to Athens and placed in Cimon's family vault.[16]The abrupt end to Thucydides's narrative, which breaks off in the middle of the year 411 BC, has traditionally been interpreted as indicating that he died while writing the book, although other explanations have been put forward.

Thucydides admired Pericles, approving of his power over the people and showing a marked distaste for the demagogues who followed him. He did not approve of the democratic mob nor the radical democracy that Pericles ushered in but considered democracy acceptable when guided by a good leader.[20] Thucydides's presentation of events is generally even-handed; for example, he does not minimize the negative effect of his own failure at Amphipolis. Occasionally, however, strong passions break through, as in his scathing appraisals of the demagogues Cleon;[21][22] and Hyperbolus.[23] Cleon has sometimes been connected with Thucydides's exile.[24]

That Thucydides was clearly moved by the suffering inherent in war and concerned about the excesses to which human nature is prone in such circumstances is evident in his analysis of the atrocities committed during civil conflict on Corcyra,[25] which includes the phrase "War is a violent teacher" (Greek πόλεμος βίαιος διδάσκαλος).

The History of the Peloponnesian War

After his death, Thucydides's history was subdivided into eight books: its modern title is the History of the Peloponnesian War. His great contribution to history and historiography is contained in this one dense history of the 27-year war between Athens and Sparta, each with their respective allies. This subdividing was most likely done by librarians and archivists, themselves being historians and scholars, most likely working in the Library of Alexandria.

The History of the Peloponnesian War continued to be modified well beyond the end of the war in 404, as exemplified by a reference at Book I.1.13[30] to the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War (404 BCE), seven years after the last events in the main text of Thucydides' history. [31]

Thucydides is generally regarded as one of the first true historians. Like his predecessor Herodotus, known as "the father of history", Thucydides places a high value on eyewitness testimony and writes about events in which he himself probably took part. He also assiduously consulted written documents and interviewed participants about the events that he recorded. Unlike Herodotus, whose stories often teach that a foolish arrogance invites the wrath of the gods, Thucydides does not acknowledge divine intervention in human affairs.[32]

Thucydides exerted wide historiographical influence on subsequent Hellenistic and Roman historians, though the exact description of his style in relation to many successive historians remains unclear. [33] Readers in antiquity often placed the continuation of the stylistic legacy of the History in the writings of Thucydides' putative intellectual successor Xenophon. Such readings often described Xenophon's treatises as attempts to "finish" Thucydides' History. Many of these interpretations, however, have garnered significant scepticism among modern scholars, such as Dillery, who spurn the view of interpreting Xenophon qua Thucydides, arguing that the latter's "modern" history (defined as constructed based on literary and historical themes) is antithetical to the former's account in the Hellenica, which diverges from the Hellenic historiographical tradition in its absence of a preface or introduction to the text and the associated lack of an "overarching concept" unifying the history.[34]

A noteworthy difference between Thucydides's method of writing history and that of modern historians is Thucydides's inclusion of lengthy formal speeches that, as he himself states, were literary reconstructions rather than actual quotations of what was said — or, perhaps, what he believed ought to have been said. Arguably, had he not done this, the gist of what was said would not otherwise be known at all — whereas today there is a plethora of documentation — written records, archives and recording technology for historians to consult. Therefore, Thucydides's method served to rescue his mostly oral sources from oblivion. We do not know how these historical figures actually spoke. Thucydides's recreation uses a heroic stylistic register. A celebrated example is Pericles' funeral oration, which heaps honour on the dead and includes a defence of democracy:

The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own land, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not on stone but in the hearts and minds of men. 2:43Stylistically, the placement of this passage also serves to heighten the contrast with the description of the plague in Athens immediately following it, which graphically emphasizes the horror of human mortality, thereby conveying a powerful sense of verisimilitude:

Though many lay unburied, birds and beasts would not touch them, or died after tasting them [...]. The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also in which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons who had died there, just as they were; for, as the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became equally contemptuous of the gods' property and the gods' dues. All the burial rites before in use were entirely upset, and they buried the bodies as best they could. Many from want of the proper appliances, through so many of their friends having died already, had recourse to the most shameless sepultures: sometimes getting the start of those who had raised a pile, they threw their own dead body upon the stranger's pyre and ignited it; sometimes they tossed the corpse which they were carrying on the top of another that was burning, and so went off. 2:52Thucydides omits discussion of the arts, literature or the social milieu in which the events in his book take place and in which he himself grew up. He saw himself as recording an event, not a period, and went to considerable lengths to exclude what he deemed frivolous or extraneous.

Philosophical outlook and influences

Paul Shorey thematizes Thucydides' outlook by calling him "a cynic devoid of moral sensibility."[35] In addition, he notes that Thucydides conceived of man's nature as strictly determined by the physical and social environments, alongside basic desires.[36]Thucydides' work indicates an influence from the teachings of the Sophists that contributes substantially to the thinking and character of his History[37] Possible evidence includes the skeptical ideas concerning justice and morality.[38] There are also elements within the History - such as his views on nature revolving around the factual, empirical, and the non-anthropomorphic - which permit the stipulation awareness, if not subscription to, the views of philosophers like Anaxagores and Democritus. There is also evidence of his knowledge concerning some of the corpus of Hippocratic medical writings.[39]

Thucydides is especially interested in the relationship between human intelligence and judgment,[40] Fortune and Necessity,[41] and that history, as in life, is too irrational and incalculable to predict.[42]

Critical interpretation

For Canadian historian Charles Norris Cochrane (1889–1945), Thucydides's fastidious devotion to observable phenomena, focus on cause and effect, and strict exclusion of other factors anticipates twentieth century scientific positivism. Cochrane, the son of a physician, speculated that Thucydides generally (and especially in describing the plague in Athens) was influenced by the methods and thinking of early medical writers such as Hippocrates of Kos.[44]

After World War II, Classical scholar Jacqueline de Romilly pointed out that the problem of Athenian imperialism was one of Thucydides's central preoccupations and situated his history in the context of Greek thinking about international politics. Since the appearance of her study, other scholars further examined Thucydides's treatment of realpolitik.

More recently, scholars have questioned the perception of Thucydides as simply "the father of realpolitik". Instead they have brought to the fore the literary qualities of the History, which they see as belonging to the narrative tradition of Homer and Hesiod and as concerned with the concepts of justice and suffering found in Plato and Aristotle and problematized in Aeschylus and Sophocles.[45] Richard Ned Lebow terms Thucydides "the last of the tragedians", stating that "Thucydides drew heavily on epic poetry and tragedy to construct his history, which not surprisingly is also constructed as a narrative."[46] In this view, the blind and immoderate behaviour of the Athenians (and indeed of all the other actors), though perhaps intrinsic to human nature, ultimately leads to their downfall. Thus his History could serve as a warning to future leaders to be more prudent, by putting them on notice that someone would be scrutinizing their actions with a historian's objectivity rather than a chronicler's flattery.[47]

Finally, the question has recently been raised as to whether Thucydides was not greatly, if not fundamentally, concerned with the matter of religion. Contrary to Herodotus, who portrays the gods as active agents in human affairs, Thucydides attributes the existence of the divine entirely to the needs of political life. The gods are seen as existing only in the minds of men. Religion as such reveals itself in the History to be not simply one type of social behaviour among others, but what permeates the whole of social existence, permitting the emergence of justice.[48]

Thucydides versus Herodotus

To hear this history rehearsed, for that there be inserted in it no fables, shall be perhaps not delightful. But he that desires to look into the truth of things done, and which (according to the condition of humanity) may be done again, or at least their like, shall find enough herein to make him think it profitable. And it is compiled rather for an everlasting possession than to be rehearsed for a prize. 1:22Herodotus records in his Histories not only the events of the Persian Wars but also geographical and ethnographical information, as well as the fables related to him during his extensive travels. Typically, he passes no definitive judgment on what he has heard. In the case of conflicting or unlikely accounts, he presents both sides, says what he believes and then invites readers to decide for themselves.[51] The work of Herodotus is reported to have been recited at festivals, where prizes were awarded, as for example, during the games at Olympia.[52]

Herodotus views history as a source of moral lessons, with conflicts and wars as misfortunes flowing from initial acts of injustice perpetuated through cycles of revenge.[53] In contrast, Thucydides claims to confine himself to factual reports of contemporary political and military events, based on unambiguous, first-hand, eye-witness accounts,[54] although, unlike Herodotus, he does not reveal his sources. Thucydides views life exclusively as political life, and history in terms of political history. Conventional moral considerations play no role in his analysis of political events while geographic and ethnographic aspects are omitted or, at best, of secondary importance. Subsequent Greek historians — such as Ctesias, Diodorus, Strabo, Polybius and Plutarch — held up Thucydides's writings as a model of truthful history. Lucian[55] refers to Thucydides as having given Greek historians their law, requiring them to say what had been done (ὡς ἐπράχθη). Greek historians of the fourth century BC accepted that history was political and that contemporary history was the proper domain of a historian.[56] Cicero calls Herodotus the "father of history;"[57] yet the Greek writer Plutarch, in his Moralia (Ethics) denigrated Herodotus, notably calling him a philobarbaros, a "barbarian lover', to the detriment of the Greeks.[58] Unlike Thucydides, however, these authors all continued to view history as a source of moral lessons.

Due to the loss of the ability to read Greek, Thucydides and Herodotus were largely forgotten during the Middle Ages in Western Europe, although their influence continued in the Byzantine world. In Europe, Herodotus become known and highly respected only in the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century as an ethnographer, in part due to the discovery of America, where customs and animals were encountered even more surprising than what he had related. During the Reformation, moreover, information about Middle Eastern countries in the Histories provided a basis for establishing Biblical chronology as advocated by Isaac Newton.

The first European translation of Thucydides (into Latin) was made by the humanist Lorenzo Valla between 1448 and 1452, and the first Greek edition was published by Aldo Manuzio in 1502. During the Renaissance, however, Thucydides attracted less interest among Western European historians as a political philosopher than his successor, Polybius,[59] although Poggio Bracciolini claimed to have been influenced by him. There is not much trace of Thucydides's influence in Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince (1513), which held that the chief aim of a new prince must be to "maintain his state" [i.e., his power] and that in so doing he is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion. Later historians, such as J. B. Bury, however, have noted parallels between them:

If, instead of a history, Thucydides had written an analytical treatise on politics, with particular reference to the Athenian empire, it is probable that . . . he could have forestalled Machiavelli. . . .[since] the whole innuendo of the Thucydidean treatment of history agrees with the fundamental postulate of Machiavelli, the supremacy of reason of state. To maintain a state said the Florentine thinker, "a statesman is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion." . . . But . . . the true Machiavelli, not the Machiavelli of fable. . . entertained an ideal: Italy for the Italians, Italy freed from the stranger: and in the service of this ideal he desired to see his speculative science of politics applied. Thucydides has no political aim in view: he was purely a historian. But it was part of the method of both alike to eliminate conventional sentiment and morality.[60]In the seventeenth century, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose Leviathan advocated absolute monarchy, admired Thucydides and in 1628 was the first to translate his writings into English directly from Greek. Thucydides, Hobbes and Machiavelli are together considered the founding fathers of political realism, according to which state policy must primarily or solely focus on the need to maintain military and economic power rather than on ideals or ethics.

Nineteenth-century positivist historians stressed what they saw as Thucydides's seriousness, his scientific objectivity and his advanced handling of evidence. A virtual cult following developed among such German philosophers as Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel and Friedrich Nietzsche, who claimed that, "[in Thucydides], the portrayer of man, that culture of the most impartial knowledge of the world finds its last glorious flower." The late-18th century Swiss historian Johannes von Müller described Thucydides as 'the favourite author of the greatest and noblest men, and one of the best teachers of the wisdom of human life.' [61] For Eduard Meyer, Macaulay and Leopold von Ranke, who initiated modern source-based history writing,[62] Thucydides was again the model historian.[63][64]

Generals and statesmen loved him: the world he drew was theirs, an exclusive power-brokers' club. It is no accident that even today Thucydides turns up as a guiding spirit in military academies, neocon think tanks and the writings of men like Henry Kissinger; whereas Herodotus has been the choice of imaginative novelists (Michael Ondaatje's novel The English Patient and the film based on it boosted the sale of the Histories to a wholly unforeseen degree) and — as food for a starved soul — of an equally imaginative foreign correspondent from Iron Curtain Poland, Ryszard Kapuscinski.[65]These historians also admired Herodotus, however, as social and ethnographic history increasingly came to be recognized as complementary to political history.[66] In the twentieth century, this trend gave rise to the works of Johan Huizinga, Marc Bloch and Braudel, who pioneered the study of long-term cultural and economic developments and the patterns of everyday life. The Annales School, which exemplifies this direction, has been viewed as extending the tradition of Herodotus.[67]

At the same time, Thucydides's influence was increasingly important in the area of international relations during the Cold War, through the work of Hans Morgenthau, Leo Strauss[68] and Edward Carr.[69]

The tension between the Thucydidean and Herodotean traditions extends beyond historical research. According to Irving Kristol, self-described founder of American Neoconservatism, Thucydides wrote "the favorite neoconservative text on foreign affairs";[70] and Thucydides is a required text at the Naval War College, an American institution located in Rhode Island. On the other hand, Daniel Mendelsohn, in a review of a recent edition of Herodotus, suggests that, at least in his graduate school days during the Cold War, professing admiration of Thucydides served as a form of self-presentation:

To be an admirer of Thucydides' History, with its deep cynicism about political, rhetorical and ideological hypocrisy, with its all too recognizable protagonists — a liberal yet imperialistic democracy and an authoritarian oligarchy, engaged in a war of attrition fought by proxy at the remote fringes of empire — was to advertise yourself as a hardheaded connoisseur of global Realpolitik.[71]Another author, Thomas Geoghegan, whose speciality is labour rights, comes down on the side of Herodotus when it comes to drawing lessons relevant to Americans, who, he notes, tend to be rather isolationist in their habits (if not in their political theorizing): "We should also spend more funds to get our young people out of the library where they're reading Thucydides and get them to start living like Herodotus — going out and seeing the world."[72]

Quotations

- "But, the bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it."[73]

- "Right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must."[74] — This quotation is part of the Melian dialogue (Strassler 352/5.89).

- "It is a general rule of human nature that people despise those who treat them well, and look up to those who make no concessions."[75]

- "In peace and prosperity states and individuals have better sentiments, because they do not find themselves suddenly confronted with imperious necessities; but war takes away the easy supply of daily wants and so proves a rough master that brings most men's characters to a level with their fortunes" (Strassler 199/3.82.2).

- "The cause of all these evils was the lust for power arising from greed and ambition; and from these passions proceeded the violence of parties once engaged in contention."[76]

- "So that, though overcome by three of the greatest things, honour, fear and profit, we have both accepted the dominion delivered us and refuse again to surrender it, we have therein done nothing to be wondered at nor beside the manner of men."[77]

- "Indeed men too often take upon themselves in the prosecution of their revenge to set the example of doing away with those general laws to which all can look for salvation in adversity, instead of allowing them to subsist against the day of danger when their aid may be required" (Strassler 201/3.84.3).

- "It is the habit of mankind to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not desire" (Strassler 282/4.108.4).

- "The nation that will insist upon drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking by cowards."

- "The State that separates its scholars from its warriors will have its thinking done by cowards and its fighting by fools."

Quotations about Thucydides

And after [the time of Herodotus], Thucydides, in my opinion, easily vanquished all in the artfulness of his style: he so concentrates his copious material that he almost matches the number of his words with the number of his thoughts. In his words, further, he is so apposite and compressed that you do not know whether his matter is being illuminated by his diction or his words by his thoughts. (Cicero,De Oratore 2.56 (55 B.C.))In the preface to his 1628 translation of Thucydides, entitled, Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warres, political philosopher Thomas Hobbes calls Thucydides

"the most politic historiographer that ever wrote."A hundred years later, philosopher David Hume, wrote that:

The first page of Thucydides is, in my opinion, the commencement of real history. All preceding narrations are so intermixed with fable, that philosophers ought to abandon them to the embellishments of poets and orators. ("Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations", 1742)Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that the best antidotes for Platonism were to be found in Thucydides:

"My recreation, my predilection, my cure, after all Platonism, has always been Thucydides. Thucydides and perhaps Machiavelli's Principe are most closely related to me owing to the absolute determination which they show of refusing to deceive themselves and of seeing reason in reality – not in "rationality," and still less in "morality." There is no more radical cure than Thucydides for the lamentably rose-coloured idealisation of the Greeks... His writings must be carefully studied line by line, and his unuttered thoughts must be read as distinctly as what he actually says. There are few thinkers so rich in unuttered thoughts... Thucydides is the great summing up, the final manifestation of that strong, severe positivism which lay in the instincts of the ancient Hellene. After all, it is courage in the face of reality that distinguishes such natures as Thucydides from Plato: Plato is a coward in the face of reality – consequently he takes refuge in the ideal: Thucydides is a master of himself – consequently he is able to master life." (A Nietzsche Compendium, Twilight of the Idols, trans. Anthony M. Ludovici)W. H. Auden's poem, "September 1, 1939", written at the start of World War II, contains these lines:

Exiled Thucydides knew All that a speech can say About Democracy, And what dictators do, The elderly rubbish they talk To an apathetic grave; Analysed all in his book, The enlightenment driven away, The habit-forming pain, Mismanagement and grief: We must suffer them all again.

| Thucydides | |

|---|---|

Plaster cast bust of Thucydides (in the Pushkin Museum). From a Roman copy (located at Holkham Hall) of an early 4th Century BC Greek original.

|

|

| Native name | Θουκυδίδης |

| Born | c. 460 BC Halimous (modern Alimos) |

| Died | c. 400 BC (aged approximately 60) Athens |

| Ethnicity | Greek |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Notable work | History of the Peloponnesian War |

| Relatives | Olorus (father) |

He has also been called the father of the school of political realism, which views the political behavior of individuals and the subsequent outcome of relations between states as ultimately mediated by and constructed upon the emotions of fear and self-interest.[3] His text is still studied at both universities and advanced military colleges worldwide.[4] The Melian dialogue remains a seminal work of international relations theory while Pericles' Funeral Oration is widely studied in political theory, history, and classical studies.

More generally, Thucydides showed an interest in developing an understanding of human nature to explain behaviour in such crises as plague, massacres, as in that of the Melians, and civil war.

Life

In spite of his stature as a historian, modern historians know relatively little about Thucydides's life. The most reliable information comes from his own History of the Peloponnesian War, which expounds his nationality, paternity and native locality. Thucydides informs us that he fought in the war, contracted the plague and was exiled by the democracy. He may have also been involved in quelling the Samian Revolt.[5]Evidence from the Classical period

Thucydides identifies himself as an Athenian, telling us that his father's name was Olorus and that he was from the Athenian deme of Halimous.[6] He survived the Plague of Athens[7] that killed Pericles and many other Athenians. He also records that he owned gold mines at Scapte Hyle (literally: "Dug Woodland"), a coastal area in Thrace, opposite the island of Thasos.[8]Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance, and news of its fall caused great consternation in Athens.[11] It was blamed on Thucydides, although he claimed that it was not his fault and that he had simply been unable to reach it in time. Because of his failure to save Amphipolis, he was sent into exile:[12]

I lived through the whole of it, being of an age to comprehend events, and giving my attention to them in order to know the exact truth about them. It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly.Using his status as an exile from Athens to travel freely among the Peloponnesian allies, he was able to view the war from the perspective of both sides. During his exile from Athens, Thucydides wrote his most famous work "History of the Peloponnesian War." Because he was in exile during this time, he was free to speak his mind. He also conducted important research for his history during this time, having claimed that he pursued the project as he thought it would be one of the greatest wars waged among the Greeks in terms of scale. This is all that Thucydides wrote about his own life, but a few other facts are available from reliable contemporary sources. Herodotus wrote that the name Όloros, Thucydides's father's name, was connected with Thrace and Thracian royalty.[13] Thucydides was probably connected through family to the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, and his son Cimon, leaders of the old aristocracy supplanted by the Radical Democrats. Cimon's maternal grandfather's name was also Olorus, making the connection exceedingly likely. Another Thucydides lived before the historian and was also linked with Thrace, making a family connection between them very likely as well. Finally, Herodotus confirms the connection of Thucydides's family with the mines at Scapté Hýlē.[14]

Combining all the fragmentary evidence available, it seems that his family had owned a large estate in Thrace, one that even contained gold mines, and which allowed the family considerable and lasting affluence. The security and continued prosperity of the wealthy estate must have necessitated formal ties with local kings or chieftains, which explains the adoption of the distinctly Thracian royal name "Όloros" into the family. Once exiled, Thucydides took permanent residence in the estate and, given his ample income from the gold mines, he was able to dedicate himself to full-time history writing and research, including many fact-finding trips. In essence, he was a well-connected gentleman of considerable resources who, by then retired from the political and military spheres, decided to fund his own historical project.

Later sources

The remaining evidence for Thucydides's life comes from rather less reliable later ancient sources. According to Pausanias, someone named Oenobius was able to get a law passed allowing Thucydides to return to Athens, presumably sometime shortly after the city's surrender and the end of the war in 404 BC.[15] Pausanias goes on to say that Thucydides was murdered on his way back to Athens. Many doubt this account, seeing evidence to suggest he lived as late as 397 BC. Plutarch claims that his remains were returned to Athens and placed in Cimon's family vault.[16]The abrupt end to Thucydides's narrative, which breaks off in the middle of the year 411 BC, has traditionally been interpreted as indicating that he died while writing the book, although other explanations have been put forward.

Thucydides admired Pericles, approving of his power over the people and showing a marked distaste for the demagogues who followed him. He did not approve of the democratic mob nor the radical democracy that Pericles ushered in but considered democracy acceptable when guided by a good leader.[20] Thucydides's presentation of events is generally even-handed; for example, he does not minimize the negative effect of his own failure at Amphipolis. Occasionally, however, strong passions break through, as in his scathing appraisals of the demagogues Cleon;[21][22] and Hyperbolus.[23] Cleon has sometimes been connected with Thucydides's exile.[24]

That Thucydides was clearly moved by the suffering inherent in war and concerned about the excesses to which human nature is prone in such circumstances is evident in his analysis of the atrocities committed during civil conflict on Corcyra,[25] which includes the phrase "War is a violent teacher" (Greek πόλεμος βίαιος διδάσκαλος).

The History of the Peloponnesian War

After his death, Thucydides's history was subdivided into eight books: its modern title is the History of the Peloponnesian War. His great contribution to history and historiography is contained in this one dense history of the 27-year war between Athens and Sparta, each with their respective allies. This subdividing was most likely done by librarians and archivists, themselves being historians and scholars, most likely working in the Library of Alexandria.

The History of the Peloponnesian War continued to be modified well beyond the end of the war in 404, as exemplified by a reference at Book I.1.13[30] to the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War (404 BCE), seven years after the last events in the main text of Thucydides' history. [31]

Thucydides is generally regarded as one of the first true historians. Like his predecessor Herodotus, known as "the father of history", Thucydides places a high value on eyewitness testimony and writes about events in which he himself probably took part. He also assiduously consulted written documents and interviewed participants about the events that he recorded. Unlike Herodotus, whose stories often teach that a foolish arrogance invites the wrath of the gods, Thucydides does not acknowledge divine intervention in human affairs.[32]

Thucydides exerted wide historiographical influence on subsequent Hellenistic and Roman historians, though the exact description of his style in relation to many successive historians remains unclear. [33] Readers in antiquity often placed the continuation of the stylistic legacy of the History in the writings of Thucydides' putative intellectual successor Xenophon. Such readings often described Xenophon's treatises as attempts to "finish" Thucydides' History. Many of these interpretations, however, have garnered significant scepticism among modern scholars, such as Dillery, who spurn the view of interpreting Xenophon qua Thucydides, arguing that the latter's "modern" history (defined as constructed based on literary and historical themes) is antithetical to the former's account in the Hellenica, which diverges from the Hellenic historiographical tradition in its absence of a preface or introduction to the text and the associated lack of an "overarching concept" unifying the history.[34]

A noteworthy difference between Thucydides's method of writing history and that of modern historians is Thucydides's inclusion of lengthy formal speeches that, as he himself states, were literary reconstructions rather than actual quotations of what was said — or, perhaps, what he believed ought to have been said. Arguably, had he not done this, the gist of what was said would not otherwise be known at all — whereas today there is a plethora of documentation — written records, archives and recording technology for historians to consult. Therefore, Thucydides's method served to rescue his mostly oral sources from oblivion. We do not know how these historical figures actually spoke. Thucydides's recreation uses a heroic stylistic register. A celebrated example is Pericles' funeral oration, which heaps honour on the dead and includes a defence of democracy:

The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own land, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not on stone but in the hearts and minds of men. 2:43Stylistically, the placement of this passage also serves to heighten the contrast with the description of the plague in Athens immediately following it, which graphically emphasizes the horror of human mortality, thereby conveying a powerful sense of verisimilitude:

Though many lay unburied, birds and beasts would not touch them, or died after tasting them [...]. The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also in which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons who had died there, just as they were; for, as the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became equally contemptuous of the gods' property and the gods' dues. All the burial rites before in use were entirely upset, and they buried the bodies as best they could. Many from want of the proper appliances, through so many of their friends having died already, had recourse to the most shameless sepultures: sometimes getting the start of those who had raised a pile, they threw their own dead body upon the stranger's pyre and ignited it; sometimes they tossed the corpse which they were carrying on the top of another that was burning, and so went off. 2:52Thucydides omits discussion of the arts, literature or the social milieu in which the events in his book take place and in which he himself grew up. He saw himself as recording an event, not a period, and went to considerable lengths to exclude what he deemed frivolous or extraneous.

Philosophical outlook and influences

Paul Shorey thematizes Thucydides' outlook by calling him "a cynic devoid of moral sensibility."[35] In addition, he notes that Thucydides conceived of man's nature as strictly determined by the physical and social environments, alongside basic desires.[36]Thucydides' work indicates an influence from the teachings of the Sophists that contributes substantially to the thinking and character of his History[37] Possible evidence includes the skeptical ideas concerning justice and morality.[38] There are also elements within the History - such as his views on nature revolving around the factual, empirical, and the non-anthropomorphic - which permit the stipulation awareness, if not subscription to, the views of philosophers like Anaxagores and Democritus. There is also evidence of his knowledge concerning some of the corpus of Hippocratic medical writings.[39]

Thucydides is especially interested in the relationship between human intelligence and judgment,[40] Fortune and Necessity,[41] and that history, as in life, is too irrational and incalculable to predict.[42]

Critical interpretation

For Canadian historian Charles Norris Cochrane (1889–1945), Thucydides's fastidious devotion to observable phenomena, focus on cause and effect, and strict exclusion of other factors anticipates twentieth century scientific positivism. Cochrane, the son of a physician, speculated that Thucydides generally (and especially in describing the plague in Athens) was influenced by the methods and thinking of early medical writers such as Hippocrates of Kos.[44]

After World War II, Classical scholar Jacqueline de Romilly pointed out that the problem of Athenian imperialism was one of Thucydides's central preoccupations and situated his history in the context of Greek thinking about international politics. Since the appearance of her study, other scholars further examined Thucydides's treatment of realpolitik.

More recently, scholars have questioned the perception of Thucydides as simply "the father of realpolitik". Instead they have brought to the fore the literary qualities of the History, which they see as belonging to the narrative tradition of Homer and Hesiod and as concerned with the concepts of justice and suffering found in Plato and Aristotle and problematized in Aeschylus and Sophocles.[45] Richard Ned Lebow terms Thucydides "the last of the tragedians", stating that "Thucydides drew heavily on epic poetry and tragedy to construct his history, which not surprisingly is also constructed as a narrative."[46] In this view, the blind and immoderate behaviour of the Athenians (and indeed of all the other actors), though perhaps intrinsic to human nature, ultimately leads to their downfall. Thus his History could serve as a warning to future leaders to be more prudent, by putting them on notice that someone would be scrutinizing their actions with a historian's objectivity rather than a chronicler's flattery.[47]

Finally, the question has recently been raised as to whether Thucydides was not greatly, if not fundamentally, concerned with the matter of religion. Contrary to Herodotus, who portrays the gods as active agents in human affairs, Thucydides attributes the existence of the divine entirely to the needs of political life. The gods are seen as existing only in the minds of men. Religion as such reveals itself in the History to be not simply one type of social behaviour among others, but what permeates the whole of social existence, permitting the emergence of justice.[48]

Thucydides versus Herodotus

To hear this history rehearsed, for that there be inserted in it no fables, shall be perhaps not delightful. But he that desires to look into the truth of things done, and which (according to the condition of humanity) may be done again, or at least their like, shall find enough herein to make him think it profitable. And it is compiled rather for an everlasting possession than to be rehearsed for a prize. 1:22Herodotus records in his Histories not only the events of the Persian Wars but also geographical and ethnographical information, as well as the fables related to him during his extensive travels. Typically, he passes no definitive judgment on what he has heard. In the case of conflicting or unlikely accounts, he presents both sides, says what he believes and then invites readers to decide for themselves.[51] The work of Herodotus is reported to have been recited at festivals, where prizes were awarded, as for example, during the games at Olympia.[52]

Herodotus views history as a source of moral lessons, with conflicts and wars as misfortunes flowing from initial acts of injustice perpetuated through cycles of revenge.[53] In contrast, Thucydides claims to confine himself to factual reports of contemporary political and military events, based on unambiguous, first-hand, eye-witness accounts,[54] although, unlike Herodotus, he does not reveal his sources. Thucydides views life exclusively as political life, and history in terms of political history. Conventional moral considerations play no role in his analysis of political events while geographic and ethnographic aspects are omitted or, at best, of secondary importance. Subsequent Greek historians — such as Ctesias, Diodorus, Strabo, Polybius and Plutarch — held up Thucydides's writings as a model of truthful history. Lucian[55] refers to Thucydides as having given Greek historians their law, requiring them to say what had been done (ὡς ἐπράχθη). Greek historians of the fourth century BC accepted that history was political and that contemporary history was the proper domain of a historian.[56] Cicero calls Herodotus the "father of history;"[57] yet the Greek writer Plutarch, in his Moralia (Ethics) denigrated Herodotus, notably calling him a philobarbaros, a "barbarian lover', to the detriment of the Greeks.[58] Unlike Thucydides, however, these authors all continued to view history as a source of moral lessons.

Due to the loss of the ability to read Greek, Thucydides and Herodotus were largely forgotten during the Middle Ages in Western Europe, although their influence continued in the Byzantine world. In Europe, Herodotus become known and highly respected only in the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century as an ethnographer, in part due to the discovery of America, where customs and animals were encountered even more surprising than what he had related. During the Reformation, moreover, information about Middle Eastern countries in the Histories provided a basis for establishing Biblical chronology as advocated by Isaac Newton.

The first European translation of Thucydides (into Latin) was made by the humanist Lorenzo Valla between 1448 and 1452, and the first Greek edition was published by Aldo Manuzio in 1502. During the Renaissance, however, Thucydides attracted less interest among Western European historians as a political philosopher than his successor, Polybius,[59] although Poggio Bracciolini claimed to have been influenced by him. There is not much trace of Thucydides's influence in Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince (1513), which held that the chief aim of a new prince must be to "maintain his state" [i.e., his power] and that in so doing he is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion. Later historians, such as J. B. Bury, however, have noted parallels between them:

If, instead of a history, Thucydides had written an analytical treatise on politics, with particular reference to the Athenian empire, it is probable that . . . he could have forestalled Machiavelli. . . .[since] the whole innuendo of the Thucydidean treatment of history agrees with the fundamental postulate of Machiavelli, the supremacy of reason of state. To maintain a state said the Florentine thinker, "a statesman is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion." . . . But . . . the true Machiavelli, not the Machiavelli of fable. . . entertained an ideal: Italy for the Italians, Italy freed from the stranger: and in the service of this ideal he desired to see his speculative science of politics applied. Thucydides has no political aim in view: he was purely a historian. But it was part of the method of both alike to eliminate conventional sentiment and morality.[60]In the seventeenth century, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose Leviathan advocated absolute monarchy, admired Thucydides and in 1628 was the first to translate his writings into English directly from Greek. Thucydides, Hobbes and Machiavelli are together considered the founding fathers of political realism, according to which state policy must primarily or solely focus on the need to maintain military and economic power rather than on ideals or ethics.