Ian recorded his second solo album in NYC, and this finds him in an altogether softer mood - there are none of Ian's trademark rockers on this album. Management differences meant that Mick Ronson was absent ("I'll never work with Mick again so long as Tony DeFries is his manager" - Ian), adding evidence that at least partially Boy included management as a target, so Ian brought in Chris Stainton on keyboards to act as a balancing force in the studio ("I need someone who'll argue with me"). The album featured a first-class coterie of musicians including the terrific David Sanborn on sax, humorously revealed by Ian that he was in the loo during his solo.

Highlight of the album is Irene Wilde (which Ian maintains is a true story), and You Nearly Did Me In (which features Queen's Freddie Mercury, Brian May and Roger Taylor on backing vocals).

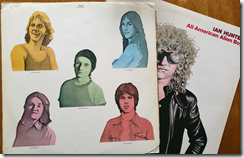

The 2006 reissue sees excellent sound quality, and a host of bonus tracks none of which have been released before. It also comes with an excellent booklet written by Campbell Devine. The original version of Rape has been restored, which some may see as a disappointment compared with the rare intro on the previous 1998 CD.

This is the third release of this album on CD. This album was previously available on a USA CD. Sound quality was good, considering that by all accounts the master tapes were not in good shape. No bonus tracks. In 1998 this album was issued in the UK as part of Sony's Rewind series. Sound quality was excellent, audibly better than the USA CD. The 1998 CD also came with a previously-unavailable version of Rape, which had the Singin' In The Rain intro. This version was previously available only on a few US test pressings and had never been issued officially before!

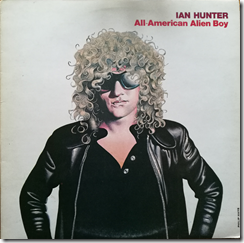

All American Alien Boy is the second studio album by Ian Hunter. Because of management issues, Mick Ronson did not appear on this album;[3] instead, Hunter brought in keyboardist Chris Stainton to act as a balancing force in the studio. Unlike his previous album, the album didn't feature any of his trademark rockers (apart from "Restless Youth") and he opted for a more jazzy direction including bassist Jaco Pastorius. The album title is a play on Rick Derringer's 1973 album All American Boy.[citation needed] Queen appear as backing vocalists on the track "You Nearly Did Me In".

In 2006, the album was reissued with several bonus tracks.

Track listing[edit]

All songs written by Ian Hunter.

Side one

- "Letter to Britannia from the Union Jack" – 3:48

- "All American Alien Boy" – 7:07

- "Irene Wilde" – 3:43

- "Restless Youth" – 6:17

Side two

- "Rape" – 4:20

- "You Nearly Did Me In" – 5:46

- "Apathy 83" – 4:43

- "God (Take 1)" – 5:45

30th Anniversary bonus tracks

- "To Rule Britannia from Union Jack" (session outtake) – 4:08

- "All American Alien Boy" (early single version) – 4:03

- "Irene Wilde (Number One)" (session outtake) – 3:53

- "Weary Anger" (session outtake) – 5:45

- "Apathy" (session outtake) – 4:42

- "(God) Advice to a Friend" (session outtake) – 5:34

Charts[edit]

| Chart (1976) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian (Kent Music Report) | 63[4] |

Personnel[edit]

- Ian Hunter – lead vocals, rhythm guitar, piano on "All American Alien Boy", backing vocals

- Chris Stainton – piano, organ, mellotron, bass guitar on "Restless Youth"

- Jaco Pastorius – bass guitar all tracks, guitar on track "God (Take I)"

- Aynsley Dunbar – drums

- Jerry Weems – lead guitar

- David Sanborn – saxophone

- Dominic Cortese – accordion

- Cornell Dupree – guitar on "Letter to Brittania From the Union Jack"

- Don Alias – congas

- Arnie Lawrence – clarinet

- Dave Bargeron – trombone

- Lewis Soloff – trumpet

- Freddie Mercury – backing vocals on "You Nearly Did Me In"

- Brian May – backing vocals on "You Nearly Did Me In"

- Roger Taylor – backing vocals on "You Nearly Did Me In"

- Bob Segarini – backing vocals

- Ann E. Sutton – backing vocals

- Gail Kantor – backing vocals

- Erin Dickins – backing vocals

ALL AMERICAN ALIEN BOY

All American Alien Boy (April 1976)

CBS 81310

UK: 29 US: 177

Since a second Hunter-Ronson album was out of the question, Ian Hunter assembled a new band for his second solo album. It was an excellent one, with Jaco Pastorius on bass, Chris Stainton on piano and organ, Gerry Weems on guitar, David Sanborn on sax, and Aynsley Dunbar on drums.

The strength of this jazz-flavoured band along with Hunter’s experiences as a new resident of the USA inspired some of the most thoughtful lyrics he would ever write.

Letter to Britannia from the Union Jack is a melancholic look at his old home country, which he saw as “a victim of your history,” a nation with a glorious past but a sadly unglorious present. The backing is tuneful but sombre.

All-American Alien Boy is more up-beat, a pounding seven-minute monologue on being a “whitey from blighty”, with prominent bass from Pastorius, fine guitar work from Weems, combined with Sanborn’s sax and female backing vocals to make a collage of sound. Hunter’s singing is somewhat recessed in the mix, but full of passion and with some memorable lines, such as “up and down the M1 in some luminous yo-yo toy”, or “the women came from heaven, the men came out of some store.” One of my favourites.

Irene Wilde is a more traditional Hunter ballad, and a song he still performs. A true story, says Hunter, based on his teenage angst encountering a girl he fancied at a bus station, who made it clear that dating was out of the question. Great melody, gentle backing and a heartfelt delivery.

Restless Youth, which closes side one, is the nearest this album has to a rocker, about a troubled boy in New York who is killed by a cop. Hunter blames his fate on “politician thieves.” As a political statement it’s not convincing, but it does chime with Hunter’s general view that the kids are all right, or would be if properly treated.

Side two opens with Rape, which describes (I think) a young man who commits a rape but gets off scot free because he is “sick rich and stoned” and has a good lawyer. “Justice just is Not!” is the punning conclusion. Hunter’s mentor Bob Dylan does this sort of song better; but it is a strong number nevertheless.

Next up is You Nearly Did Me In, which remarkably has most of Queen on backing vocals. The story is that Queen (who had toured with Mott the Hoople) just happened to be visiting the studio at the right time. It’s another highlight of the album, a song possibly about drug addicts, “lost children of the night”, with a great chorus, though exactly why the narrator is nearly “done in” has never been clear to me. The close of the song is epic though. “What ever happened to dignity? What ever happened to integrity? What ever happened to honesty?” Sanborn’s alto sax is gorgeous on this song.

Apathy 83 is a kind of reprise to the song by the Stones, and according to Devine the title was handed to Hunter by none other than Bob Dylan, after what they considered a poor Stones concert at Madison Square Garden in New York. The two happened to meet soon after; Dylan asked Hunter what he thought of the Stones concert. “Insipid,” sand Hunter. Dylan replied, “yeah, apathy for the devil.”

The song takes that thought and applies it to the politics of the time; apathy is allowing evil to flourish. To my mind this is one of Hunter’s best political statements as he rants against misdeeds in high places. Nice accordion from Dominic Cortese.

The album closes with God (Take 1), a dylanesque song in which Hunter explores religion. “I wanted to let people hear how it would sound if I really imitated Bob Dylan,” said Hunter. The song is perhaps my least favourite on the album though, rather ponderous.

All American Alien Boy is distinctive in Hunter’s solo career, beautifully performed, expertly sung, lyrically thoughtful, melodic and jazz-tinged. It was well reviewed but, says Hunter, “pretty boring on one level.” It was a huge departure from the raucous energy of Mott the Hoople, much more so than the album before it. The kids couldn’t relate and sales were disappointing. “The fact that it died commercially was a total bummer,” says Hunter.

In a recent interview with Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott, the two reflect on the album. Hunter reminds us why Ronson was not on the album. “Mick was still with Tony [Defries]. Mick was going to get more than I got, so I said no,” he says.

“You put out Alien boy,” says Elliott. “I’m 16 years old, and … what are you doing? You’ve made this album for my dad. I want more of the first records. Where’s all the rockers? It’s all very clever clever.”

“By the time I was the age you were when you made that record, all of a sudden that record made sense to me,” Elliott continues. “It took 20 years but I got it. The title track is phenomenal, because not only is it an incredible delivery, like rap before rap, it’s got the most incredibly beautiful bass playing by Jaco Pastorius, absolutely stunning, but it took me years to get my head around it.”

Hunter says it was Ronson’s favourite record of his, eventually, though not at the time.

Me, I love the album, though I wish it ended with Apathy ’83.

Robert Christgau

Robert Thomas Christgau (/ˈkrɪstɡaʊ/ KRIST-gow; born April 18, 1942) is an American music journalist and essayist. Among the most well-known[1] and influential music critics,[2] he began his career in the late 1960s as one of the earliest professional rock critics and later became an early proponent of musical movements such as hip hop, riot grrrl, and the import of African popular music in the West.[1] Christgau spent 37 years as the chief music critic and senior editor for The Village Voice, during which time he created and oversaw the annual Pazz & Jop critics poll. He has also covered popular music for Esquire, Creem, Newsday, Playboy, Rolling Stone, Billboard, NPR, Blender, and MSN Music, and was a visiting arts teacher at New York University.[3] CNN senior writer Jamie Allen has called Christgau "the E. F. Hutton of the music world – when he talks, people listen."[4]

All-American Alien Boy [Columbia, 1976]

The concept fails. Hunter isn't even a one-star generalizer, and he obviously lacks that rare knack for the political song, though the bit about needing both the left wing and the right to fly is sharp (and scary). Yet the attempt at protest is gratifying, at least as honest as it is confused. At odd moments the music kicks a line like "Justice would seem to be bored" all the way home; "Irene Wilde," a throw-in about young love, is a small treasure; and "God (Take 1)" is nice Ferlinghetti-style doggerel. So while I can't recommend, I kind of like. B-

Hunter's star-filled next album, 1976's All American Alien Boy, was recorded in the new environs of New York's Electric Lady Studios. While Mick Ronson didn't join in, All American Alien Boy saw producer-artist Hunter accompanied by jazz greats David Sanborn and Jaco Pastorius, as well as Mothers of Invention drummer Aynsley Dunbar, Blood Sweat and Tears' Lew Soloff and Dave Bargeron, and even Freddie Mercury, Brian May and Roger Taylor of Queen. The loose concept album was inspired by Hunter's travels throughout America, and largely embraced a more sophisticated, less overtly aggressive rock sound. Messrs. Mercury, Taylor and May can be heard, along with Sanborn, on "You Nearly Did Me In," one of its five songs reprised here. In Ronson's absence, Chris Stainton was brought onboard as a creative foil for Hunter, and supplied the album's evocative keyboards and organs. Aynsley Dunbar's drums shine on "Apathy 83," and Pastorius' signature bass commands attention throughout. Soloff and Bargeron, of the Blood Sweat and Tears horn section, brought their powerful brass to the epic title track which is heard here in its shorter, unique single version. Though the album failed to chart, it's today recognized one of Hunter's finest hours, as can be clearly heard on the selections here.

AMERICA HAS been good for Ian Hunter. The self portrait he paints on his second solo album All American Alien Boy retains his distinctly British character while broadening his musical horizons with large chunks of americanised rhythms. After all, how could he fail living in the land of Coca-Cola and Bob Dylan?